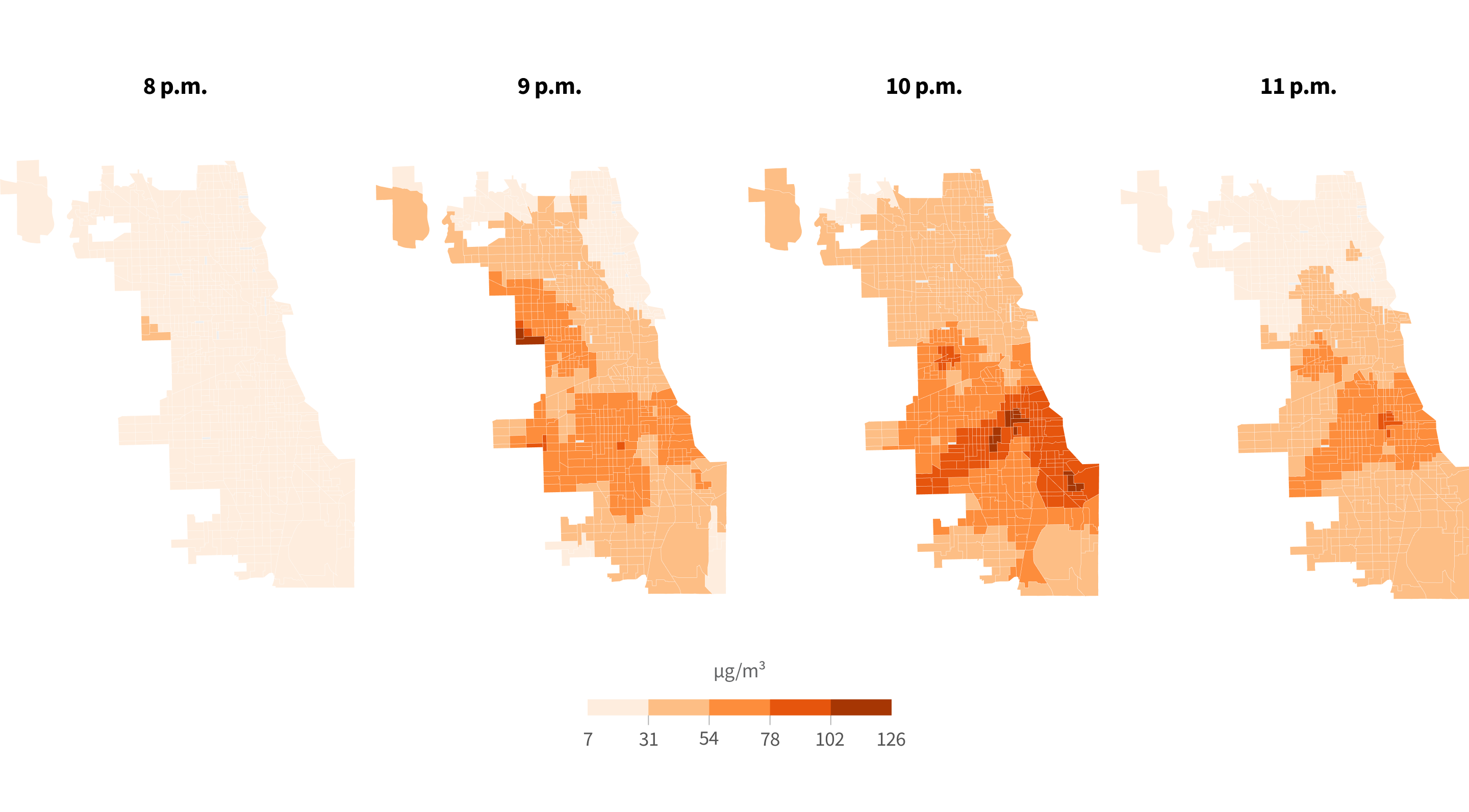

At about 8 p.m. on the Fourth of July last year, air pollution levels across Chicago started to climb. Just a few hours later, as Chicagoans watched brightly-colored fireworks explode in the sky, the city reached a level of air pollution more than four times the hourly average of a normal summer evening.

The hours between 9 p.m. and midnight on July 4, 2021, ranked as the most intensely polluted hours the city experienced at any point over the past year, according to analysis of data on Chicago’s air quality. The new analysis is part of an ongoing project about air quality by MuckRock, WBEZ and the Sun-Times.

While the findings, from a first-of-its-kind data analysis of Microsoft air sensors installed in more than 100 locations across Chicago, are not surprising, experts say, they underscore how holiday traditions like fireworks can contribute to poor air quality in a short amount of time. Researchers found similar spikes in particulate matter, or PM2.5, in Los Angeles on the Fourth, and noted it produced as much smoke as a moderate wildfire. Like Los Angeles, Chicago has among the worst air pollution of any major city in the U.S., and some of the country’s highest rates of childhood asthma, resulting in a dangerous mix for those most vulnerable.

In response to the findings, the Chicago Department of Public Health said in a statement that while it’s against the law to use fireworks in Chicago and Illinois, those laws are ineffective when they are not “regionally applied and surrounding states are more lenient in the sale and use of fireworks.”

Most types of fireworks, including bottle rockets and Roman candles, are illegal in Illinois but can be purchased in neighboring Indiana.

The city’s health department also said the new data “highlights how disproportionately elevated PM2.5 is in the South and West Sides and can affect the health of vulnerable populations, emphasizing the importance of addressing environmental justice and education about the hazardous effects of using fireworks.”

Microsoft has led a project to build a hyperlocal air quality sensor network citywide. Dr. Precious Esie, a recent doctoral graduate of Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health program, was a Microsoft research intern last summer when she noticed the spike in air pollution on Fourth of July and the unequal effect on the South and West Sides of the city, which has higher rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases.

Last year, Adam Niermann, a 43-year-old Irving Park resident and father of three, was just arriving at a park near his home as the city’s air began to fill up with fireworks and pollutants. Niermann’s neighborhood usually follows the same Independence Day traditions: a kid’s bike parade, backyard barbecues and families waiting for the sun to go down and the fireworks to start.

Chicago’s official fireworks go off over the water near Navy Pier, often before the official holiday, with this year’s display taking place on Saturday. Much of the smoke and haze Chicagoans observe on the evening of the Fourth come from individual caches and neighborhood fireworks shows.

At a park near Niermann’s home, families and kids from around the neighborhood gather for a do-it-yourself display of fireworks bought by parents in Indiana. Every year, Niermann said, the smoke in the air becomes so thick by the end of the night that floodlights at the park and street lights show clouds of smoke drifting in the air.

“By 10:30 at night, it’s just a hazy fog and smoke everywhere that you can see,” Niermann said.

Fireworks are used in celebrations across the world, but research shows that the pollutants released during their explosions cause short-term increases in air pollution.

Although the pollution is short-lived, the particles released contain toxic metals, like barium, manganese and copper. This brief but intense pollution can give people with respiratory diseases discomfort.

In some cases, it can cause asthma attacks and lead to hospitalization.

Our earlier reporting as part of this project showed how the South and West sides of the city, predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, suffer most from poor air quality.

During the holiday’s most intense period of pollution, around 10 p.m., five sensors in the network recorded hourly averages over 100 micrograms per cubic meter, according to our analysis. All of these sensors are on the city’s South Side — in Englewood, South Chicago, Washington Park and Ashburn.

The only area in the city that experienced more intense pollution was in Austin, at about 9 p.m., where a sensor at the Harrison and Central bus stop right next to Columbus Park reached an hourly average of 149 micrograms per cubic meter. These numbers are almost double the citywide averages for the evening, which were already double the 35 micrograms per cubic meter that the EPA has specified as the maximum amount for a daily average. While this threshold is considered dangerous by the agency, the EPA does not regulate short-term pollution events like fireworks on the Fourth of July. Rather, they look for high pollution as a daily average over multiple years.

There are several things experts say can help reduce the human health impact of Fourth of July air pollution.

At home, people should keep the windows closed and the air conditioning on, experts say. Wearing a N95 or KN95 mask can reduce exposure to firework pollution, said Dr. Brent Stephens, a professor at Illinois Institute of Technology who leads a research team that focuses on indoor and outdoor air pollution.

Attending a municipal firework show rather than using at-home fireworks reduces the amount of fireworks on the holiday and ensures a larger distance between people and the source of the pollution.

For policymakers, the city could begin to shift away from combustion of fireworks to other types of displays, like drones, that do not produce smoke, said Dr. Shahir Masri, an air pollution scientist at the University of California, Irvine, who has studied the impact of fireworks on air pollution.

“I hope that cities get more technologically savvy,” Masri said. “If we replaced even 50% of our fireworks with light shows, that’d be a 50% reduction in pollution.”

But official municipal displays are only part of the overall fireworks footprint in Chicago, known as the City of Neighborhoods.

The Niermann family usually keeps the windows closed and air conditioning on the holiday. One of their children had lung problems as an infant, but as a father, Adam was always more worried about the highway next to their house than a single day like the Fourth of July. Knowing that celebrations of the Fourth also bring some of the worst hours of air pollution makes him think differently.

“I will definitely be paying more attention and noticing what the air quality is like on the holiday,” Niermann said.

For more on this project, check out our citywide findings; an illustrated explainer of what particulate matter is and how it’s harmful; and a callout to Chicagoans to tell us more about air pollution and its effects where they live